By David Fiske, Special to The Chronicle

Ken Perry’s letter about some local aspects of the Solomon Northup story, printed in the Chronicle issue of January 10, got me thinking about what the experiences of Northup and his family, while living in the Glens Falls area, tells us about the lives of African Americans in the 19th century. This is a matter that probably few local residents know much about today.

Thanks to the film 12 Years a Slave, the story of Solomon Northup’s kidnapping is now fairly widely known.

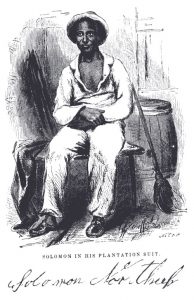

To recap: Northup was a free black living and working in Saratoga Springs, but was tricked into leaving home in 1841 and taken to Washington, D.C., where he was sold into slavery. Transported to Louisiana, he was enslaved for about a dozen years before he was fortuitously rescued and reunited with his family (who had moved from Saratoga to Glens Falls during his absence). His 1853 book, Twelve Years a Slave, was the basis for the Oscar-winning film.

When Northup was born in the early 1800s, white men and black men in New York State could vote as long as they were property owners. But in the 1820s, a new state constitution was enacted that removed the property requirement for white men…but kept it for blacks. (Later versions of the state constitution maintained this inequity, and it was not until 1870, thanks to the 15th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, that all black New York men got the vote.)

Thus, as a young man, Northup could not vote, as there is no indication he owned property. Though he was a farmer in Kingsbury for a time, he wrote in Twelve Years a Slave that he had “entered into arrangements” to obtain farmland, suggesting that it was merely leased. At other times prior to his kidnapping, he was a renter, and not a property owner.

Northup grew up during a period in which “gradual emancipation” was taking place in New York. Beginning about 1800, slaves in the state gained their freedom when they attained a certain age (which varied according to their gender and year of birth). As this process took place, the black population in the state included an odd mixture of freeborn men and women, slaves who had been freed by their owners years earlier, and some who were newly emancipated. Some white laborers saw this influx of workers as a threat to their jobs, and there was a certain amount of animosity–which politicians supported by limiting the rights of African Americans. In addition, there were unofficial restrictions on blacks, due to prejudice.

In such an environment, it is a tribute to Northup and his wife that they were able to earn sufficient income to support themselves in communities that were mostly white. Northup’s wife Ann gained a reputation as a cook at hotels in Washington, Saratoga, and Warren counties — hotels frequented by white travelers and professionals. Northup often worked alongside whites, and while taking on contracts to transport materials on the Champlain Canal, even hired white men to work under him. (Later, in 1852, when preparations were being made to locate and rescue Northup, many white residents provided affidavits in support of him.)

Having black skin exposed a person to certain hazards. In the case of Northup, he fell victim to vile men who lured blacks away from their homes and sold them as slaves in other states. Blacks also were susceptible to slavecatchers, who, in the process of hunting down runaway slaves were not overly picky about whether they had found an escaped slave or a free person whom they could sell for money.

Northup’s family, during the time he was a slave, relocated from Saratoga to Glens Falls. They resided near another black family, that of John Van Pelt. Van Pelt had also previously lived in Saratoga (where he may well have been acquainted with the Northups). In Saratoga, Van Pelt kept a barber shop and also sold subscriptions to an anti-slavery newspaper.

Records show he was born in Albany County, but his wife was born in Virginia. She probably was an escaped slave, since a suspected slavecatcher once showed up in Glen Falls looking for the Van Pelt home. Warned of this by local residents, the family was spooked enough that they moved to Canada for a while, returning to Glens Falls in the mid-1850s.

Northup’s daughter Margaret married a black man named Philip Stanton around 1849. Census information for 1850 shows the Stanton family living in Saratoga, next door to another black family that included Solomon Northup’s wife Ann and daughter Elizabeth.

Stanton had previously lived in Glens Falls, where he’d lived with his first wife, Betsey Oakley, whose mother had been a slave owned by merchant William McDonald. McDonald freed her prior to the elimination of slavery in New York in 1827. This information is from affidavits given by McDonald’s son Walter, and daughter Julia A. Arms. They also said that Philip and Betsey had been employed in their father’s house for a while after they were married. Betsey died in 1848, but she and Philip had had a child together named Charles.

Stanton and the Northup family (except Solomon, who was still in the South) had moved to Glens Falls by the early 1850s, where Stanton had purchased property. Philip and Margaret had several children: Solomon, Florence, and one who probably died very young. They lived on School Street — not far from where the Rite Aid store is now located — which would have made it easy for Ann to get to her job running the kitchen at the Glens Falls Hotel located on what is now Glen Street. (Long-time residents may remember the Rockwell House, which was at the same site.)

When Northup finally regained his freedom in 1853, he reunited with his family in Glens Falls, and set about preparing a narrative of his experiences, assisted by David Wilson, an author and lawyer who lived in Whitehall.

In the spring of 1853, Northup purchased property in Glens Falls, probably using money his publisher had paid him for the book. But soon afterward, he experienced some financial setbacks (possibly because, as one newspaper writer noted, “he is generous and pitiful to his fugitive brethren; that he gives of his substance to those who have fled from slavery, saying: ’I know what it is, I can feel for you”). Or perhaps, after years of suffering, he took to high living. At any rate, several creditors obtained judgments against him.

A mortgage on the property he’d purchased was foreclosed on by Albert N. Cheney, a prosperous dealer in lumber, early in 1855. Northup once again came into some money, however, having reached a settlement in a lawsuit he’d filed against the two men who had lured him away from Saratoga in 1841. (Information on the settlement was communicated to me by a researcher who saw paperwork which is held privately and which the owner — sadly — does not want to publicize.)

So, in May of 1855, there is another property transaction — but this time the deed lists only Ann Northup’s name, not Solomon’s. A conclusion that can be drawn is that Northup did not want his creditors to be able to come after the property. Since Northup had been traveling giving lectures about his experiences — and would continue to do so for several years from 1855 on — he may have wanted to ensure that his wife would always have a home.

From 1853 and into the 1860s, as Northup traveled about in New England, and even (at least once) to Canada, his extended family continued to reside in Glens Falls. As noted in Ken Perry’s letter, during the Civil War Charles Stanton (the son of Northup’s son-in-law from his first marriage) enlisted in the Massachusetts 54th Regiment — a unit of black soldiers — and was wounded during the assault on Battery Wagner in 1863 (this failed attack was portrayed in the film Glory).

A few weeks before the battle, Charles penned a letter to his father, which is included in a military pension file held by the National Archives. It is not clear whether the letter was received by his father or if it had been in Charles’ possession when he was taken prisoner after being wounded. The letter (which shows that Charles was not a good speller) reads, in part: “We are expected to goe to Charston, have a larg fite in a few days and if we get along wel and dont get shot we will trie to get home.”

Charles died from fever in a Confederate prison in Florence, South Carolina, a few months before the Civil War ended. Records also indicate he had been held for a while at the dreadful Andersonville prison camp.

In 1864, Ann Northup and Philip Stanton sold their adjoining properties in Glens Falls, and moved across the river to Moreau, where Stanton leased farmland from Austin K. Reynolds. This was just north of the intersection known as Reynolds Corners.

They lived there for several years, but by 1870, Ann had moved to Hudson Falls (then called Sandy Hill). The census for that year shows “Anna Northup” as a cook at a hotel run by Burton C. Dennis. During summers, Ann also had worked for some years at the Mohican House at Bolton Landing on Lake George. The hotel was run by Hiram S. Wilson, and letters he wrote during his service in the Civil War make mention of her, indicating she was a valued employee and friend.

The 1875 state census shows that the family was together once more, in Kingsbury, where Philip Stanton was a baker. No occupation is given for Ann, so she apparently no longer worked as a cook.

The census record shows her marital status as widowed, which, if correct, would mean that Solomon was deceased by then. There were some reports that he had taken to drink, but considering that he probably suffered from what we know as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, that would not be especially surprising.

Some letters written years afterward by the son of a minister who had been anti-slavery say that Northup had been involved with the underground railroad in Vermont in the early 1860s.

One letter also suggests that he was still alive as late as 1863, when he visited the minister. Some evidence suggests either that Northup took up sheep farming in Vermont, or was involved somehow in the Civil War — but the information for either scenario is very inconclusive.

It is clear, however, that Ann died in 1876, since her demise was reported in local newspapers. She apparently was working doing chores for a private family, sat down to rest, and immediately expired.

It would seem that Ann was the anchor of the family, because it dispersed after her passing. Her grandson, Solomon Northup Stanton, traveled to Iowa and Nebraska, where he got married, but then died in 1893.

Philip and Margaret Stanton, along with daughter Florence, lived in Saratoga for a short time, but then relocated to the District of Columbia, where Margaret died in 1879. Following her death, her husband and daughter (who married an African American physician) lived in Norfolk, Virginia.

Florence (Stanton) Barber was a teacher and occasionally participated in activities related to African American culture.

Overall, despite the racial prejudice that was common in those days, the Northup family overcame numerous obstacles and achieved some success and gained respect in the predominantly white communities in which they lived.

David Fiske of Ballston Spa is the author of several books, including Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave.

Copyright © 2019 Lone Oak Publishing Co., Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Glens Falls Chronicle Serving the Glens Falls/Lake George region; Warren, Washington and northern Saratoga counties since 1980

Glens Falls Chronicle Serving the Glens Falls/Lake George region; Warren, Washington and northern Saratoga counties since 1980