By Mark Frost, Chronicle Editor

Fred Fisher led the Hyde Collection during its most tumultous times, 1978-1990.

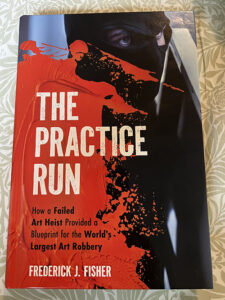

Next Thursday, May 15, his tale of those times will be published in a book called The Practice Run.

The title refers to an attempted heist of the Hyde’s art in 1980 that Mr. Fisher and others contend set the stage 10 years later for the devastating, still unsolved theft of a Vermeer, a Rembrandt and other prized works from the Gardner Museum in Boston.

The book offers a fresh take on the failed Hyde theft — and the Vanderbilt impostor who masterminded it — and attempts to strengthen the case that it links to the crime at the Gardner.

But Practice Run is also Mr. Fisher’s spiky recollection of his time in Glens Falls. He praises museum founders Louis and Charlotte Hyde, but he both criticizes and commends others and the community.

When he arrived as director in 1978, “I felt I was up to my neck in alligator-infested waters in what seemed to be a sinking ship, and I was astounded at the pervasive complacency of the board…”

When he arrived as director in 1978, “I felt I was up to my neck in alligator-infested waters in what seemed to be a sinking ship, and I was astounded at the pervasive complacency of the board…”

“The Hyde reeked of amateurism. The skeleton staff, well-intentioned as they were, were ‘playing museum.’ These were rural community folks who were given positions of responsibility beyond their means.”

He writes, “Rural Glens Falls and its surrounding region are primarily habited by a blue-collar citizenry whose interests principally center on all manner of sports activities, as well as their kids and their churches. Rembrandt, Botticelli and Picasso had little relevance for them, and unfortunately little meaning for most of the leading city fathers.”

That changed over time. It’s fair to say Mr. Fisher transformed the museum — and left exhausted by it. I remember his telling me the fight had worn him out.

Here’s a timeline of relevant moments.

When Mr. Fisher arrived in 1978, the Hyde was a struggling, perhaps failing, legacy little house art museum. “The museum was like a hundred-carat diamond hood ornament stuck on a rusty, beat-up pickup truck,” writes Mr. Fisher.

In 1985 the Hyde was upgraded enough to be accredited by the American Association of Museums.

In 1986 it launched a $5-million campaign to fund a new education wing with gallery space, studios and auditorium, restore the original Hyde house and add $2-million to its endowment. “The board, particularly Hyde family members, pledged nearly a third of the goal before the campaign went public in October,” writes Mr. Fisher.

In 1987, Aug. 26, to be exact, new board member Charley Wood held the Over The Rainbow Gala at his Great Escape theme park, donating Greta Garbow’s 1933 Duesenberg that was auctioned for $1.4-million. “In one fell swoop,” Mr. Fisher writes, “the capital campaign was moving to completion.” Mary Lou Whitney was among the gowned and tuxedoed attendees who took to The Great Escape’s rides. “My ongoing ‘Saratoga envy’ state of mind was finally shattered,” he writes.

In 1989, on Nov. 10, the expanded Hyde reopened. The Hydes’ niece Polly Beeman, “one of the loveliest and most gracious ladies I have ever had the honor of knowing,” cut the ribbon.

One day later, unbeknownst to the board Mr. Fisher says he went to interview for the executive director job at Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens, Marjorie Merriweather Post’s legacy in Washington, D.C.

In January 1990 he left for that job, which included a home on the 25-acre, gardened, guarded property and a $75-million endowment. He was unimpressed by the initial board, except the person who chaired it, who was the granddaughter of Marjorie Merriweather Post, said to have been the wealthiest woman in the world, daughter of cereal pioneer C.W. Post.

We all want to read about the attempted heist, of course, and Mr. Fisher delves into juicy details, adds some fresh ones.

The plot was set in motion when a 20-year-old purporting to be the fabulously wealthy Paul Sterling Vanderbilt arrived in Glens Falls. He lodged initially at the Queensbury Hotel, was driven about in a Bentley, successfully wooed local women, captivated their parents, was invited to move into homes and camps.

“His New England accent and the Vanderbilt lineage were very enticing,” writes Mr. Fisher. “It was, indeed, incredibly easy to be taken in my him.”

Queensbury Hotel manager Leo Turley wasn’t. In a Post-Star story by David Blow, he said, “I wouldn’t let him run up a bill…I knew he was a phony… ‘What, [a] Vanderbilt doesn’t have a credit card?’”

Vanderbilt was obsessed with the Hyde. He promised to bring it huge donations. He sought — and practically demanded — to rent the Cunningham House next door and stay there. (Hyde and Cunningham were two of three side-by-side-by-side houses built by Samuel and Eliza Jane Pruyn for their three daughters in front of the papermill that generated the family’s wealth and enabled its philanthropy.)

No, said the Whitney Museum, he had not been a board member and would never qualify that young anyway.

Those three much-in-demand IBM Selectric typewriters Vanderbilt provided? An IBM rep from Albany determined they were rentals taken from New York.

Vanderbilt — actually Brian Michael McDevitt from Swampscott, Mass. — persisted. He enlisted Michael Morey, the Queensbury Hotel’s assistant manager, in his scheme to steal artwork from the Hyde. The plot was activated as Christmas neared in 1980.

Mr. Fisher writes that in subsequent testimony Mr. Morey said he cooperated because McDevitt made threats against his five-year-old son.

“We met at Potter’s Diner in Warrensburg and went over a draft of the project,” Mr. Morey is quoted from the record.

He said he wined and dine an alarm company staffer seeking security details.

The plan was for Mr. Morey to commandeer a Federal Express truck they called to make a pick-up in South Glens Falls, and then use it to approach the museum for a purported delivery.

The FedEx driver was Mary Wingloskky of Watervliet. Mr. Fisher writes that Mr. Morey later confessed, “I handcuffed her…I gave her ether for about 15 seconds and she went under. I taped her eyes and mouth with surgical tape.”

Mr. Fisher writes, “Around 4:00 p.m., McDevitt, after determining that there were no more than four Hyde staff members in the museum, decided to drive to the designated meeting area behind Donnohue’s Meat Market” on Maple Street.

The plan was to arrive at the Hyde while some staff members were still there. They did not want to contend with an activated alarm system.

The story goes that a traffic jam on the Route 9 bridge between South Glens Falls and Glens Falls so delayed the truck that the museum closed, thwarting the heist.

Mr. Fisher adds this tidbit. Tired and used up, he wanted to go home early. His wife had the Volvo at their Coolidge Avenue home. When he called for a ride, his wife Becky said, “Honey, I can’t come right away because I’ve got to clean up after this damn dog.”

Mr. Fisher says, “I was so ready go come home that I blurted out, ‘Becky, if you can and get me right now, I’ll happily clean up the vomit.’”

And that’s why he wasn’t at the museum when the thieves arrived.

The plot collapsed, the men were arrested, then indicted for second-degree kidnapping and second-degree robbery.

“The trial ended on February 2, 1981.”

There were confessions at the South Glens Falls police station.

Times-Union reporter Ronald Kermani, whom Mr. Fisher cites as a dogged investigator and tremendous help to him, wrote, “Morey pleaded guilty to a reduced charged of attempted second-degree robbery” and was sentenced “to 60 days in jail” and five years probation.

Mr. Fisher says he talked to Mr. Morey for the book and praises him heartily. “Morey turned his misfortune into success,” creating Champlain Stone. “It has become phenomenally successful.”

McDevitt’s sentence was two years in Saratoga County jail.

He did not go straight from there. In fact, Boston police who located him after learning of the Hyde attempt brought him up on a charge of having stolen $100,000 from a Boston lawyer previously.

Mr. Fisher isn’t the first or only person who sees signs of McDevitt in the half-billion dollar heist at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum on March 18, 1990.

An Italianate home, a personal collection, a trusting target. Only two guards were on duty overnight at the Gardner — full-time music students working part-time. (The one who let the thieves in, against policy, has died, Mr. Fisher writes.) The heist was even timed for when vigilance was likely most lax. At the Hyde it was just before Christmas. At the Gardner Museum it was right after St. Patrick’s Day. The Gardner thieves purported to be police officers, as the Hyde’s duo planned to dispel doubts as FedEx staff.

The New York Times and 60 Minutes have reported on the Gardner theft and spoke of McDevitt’s possible involvement, but authorities have never given it traction. Mr. Fisher has harsh words for the investigators in the Gardner crime.

On May 27, 2004, McDevitt is said to have died. Not everybody believes it. Echoing speculation, Mr. Fisher wonders if “McDevitt was in the witness protecting program after spilling his guts about whom he was shopping for at the Gardner. That likelihood cannot be dismissed given that FBI officials claim they know who the thieves are and that they are dead.”

The Practice Run: How a Failed Art Heist Provided a Blueprint for the World’s Largest Art Robbery, by Frederick J. Fisher, will be published on May 15, 2025 by Rowman & Littlefield. It’s hard-cover, priced at $35.

The 217-page book moves right along.I read it right through the day it arrived.

Copyright © 2025 Lone Oak Publishing Co., Inc. All Rights Reserved

Glens Falls Chronicle Serving the Glens Falls/Lake George region; Warren, Washington and northern Saratoga counties since 1980

Glens Falls Chronicle Serving the Glens Falls/Lake George region; Warren, Washington and northern Saratoga counties since 1980